Or, how to learn to stop worrying and just feed your tarantula when it’s hungry.

Power feeding: The act of accelerating an animal’s growth by increasing temperatures and the amount and/or frequency it is fed.

If you’ve been in the hobby for any amount of time, you’ve likely been privy to a debate between hobbyists about the virtues or dangers of feeding tarantulas too much. Although a less incendiary topic than handling, this subject of “power feeding” still manages to elicit some strong views as folks are seemingly split over whether this is a harmless practice or a detriment to tarantulas’ health and longevity.

I’ve had many new hobbyists contact me over years needlessly worrying about whether or not they are going to overfeed their tarantulas or concerned with this horrible thing called “power feeding” that they’ve heard about and been told to avoid. When I tell folks to feed their slings as often as they want, I often get a response along the lines of, “But isn’t that power feeding? Won’t that shorten the life of my T?” I’ve even be trashed by a concerned hobbyist that told me that feeding my animals more than once a month constituted animal abuse.

Okay then…

In many ways, the term “power feeding” has become a bit of a dirty phrase to some in the hobby … which is ironic, as many informed and experienced hobbyist would argue that it doesn’t even apply to tarantulas. The term actually originated in the herp hobby, particularly when breeding color morphs of ball pythons. While snake breeders have used power feeding for decades in order to quickly get their specimens to breedable size, the practice has been recognized for having adverse effects on the animals’ health. Therefore, the assumption is that the same practice would also be harmful for arachnids.

Unfortunately, comparing snakes to tarantulas, two very different organisms, doesn’t work in this instance.

The fact is, many expert keepers feel that feeding your tarantulas as much as they will eat has no negative impact on their health and longevity. Although much has been said about the negative impacts it could have on an animal, they point to lack of scientific proof (and point to mounds of keeper anecdotal data that seems to dispel this idea). They argue that the worst that can happen from feeding a spider all it will eat is a fat tarantula that will fast for a while.

Many inexperienced hobbyists will understandably err on the side of caution and avoid this practice for the sake of their animals’ well being. They will unfortunately read about “power feeding” on some website and immediately worry that they might overfeed their pet. Due to this misinformation, they feel strongly that, by allowing their animal to “overindulge”, they are putting its health and lifespan at risk.

However, are they really extending their tarantulas’ lifespans, or is the idea of “power feeding” tarantulas only a myth?

First off, how would one “power feed” tarantulas?

Before we get any further, it’s important to define what supposedly constitutes “power feeding.” Although most folks think power feeding is just increasing the amount of food you give to your tarantula, it’s not quite that simple. To truly power feed, you need to do two things:

- Increase the temperature: To get the quick growth “power feeding” is meant to promote, you also need to stimulate the T’s metabolism. This is done by increasing the temperatures to the low 80s for most species. Basically, the warmer the surroundings, the faster your tarantulas will grow. If the temperature in your home is dipping to 68° F (20° C), then your T will not have the fast metabolism required for quick growth. For true “power feeding”, it’s more about speeding up the metabolism than just pumping your T full of food.

- Feed the tarantula as much as it will eat: With its metabolism sped up, it’s now time to increase the frequency food is offered. This can be every day or every couple days, depending on the size of the meal. If you give your .5″ sling a medium cricket to scavenge feed on, it might only be need to be fed a couple more times before it’s ready to molt. If you are feeding smaller, more manageable-sized prey, then it may eat every day to every other day.

It’s really that simple. Unfortunately, many folks will try to feed their Ts more without providing a warmer environment. Doing so will likely result in a fat T who takes its time molting (trust me … I’ve done it). It’s important to remember that higher temperatures have more to do with growth rate than how often you feed.

Now, some folks seem to consider it “power feeding” when you feed a slings multiple times a week. Personally, I think that’s a bit ridiculous. Many tarantulas are at their most voracious when they are slings, and this is a great time to make sure they get as much food as they can take. If the temperatures are high enough, and they are well-fed, this will lead to faster growth (and get your animal out of the delicate sling stage earlier).

Many hobbyists reason that tarantulas know what they are doing; if they want to eat, they’ll eat. If they’re not hungry, they won’t. In the wild, it behooves a sling to grow as fast as possible to outgrow this vulnerable stage. As slings, these animals are at particular risk from predators and the elements. During times when prey is plentiful, they would likely eat as much and as often as possible in order to foster faster growth.

So, why wouldn’t this hold true in captivity?

Even in captivity, tarantulas are most vulnerable during their sling stage. At this time, they are prone to dehydration and extra susceptible to environmental factors like humidity and temperature. Many, if not most, of the sudden deaths reported by keepers are spiderlings. Therefore, many keepers will feed their sling much more often

Personally, I tend to feed my slings as much as they’ll eat in the summer when the temps are around 80 or so for just this reason. Once the sling hits about 1.25-1.5″, I slow the feeding down to one or twice a week (depending on the size of the prey). This has worked very well for me.

Is feeding slings as much as they will eat really “power feeding”? Most experienced keepers would argue NO. Eating while food is available is a natural adaptation that allows for them to quickly grow in the wild.

But what about the adults? Again, many would argue that the “power feeding” really doesn’t apply, at least not in the way it does with snakes. Keepers have discovered that tarantulas will only eat until a certain point, then they stop and prepare to molt. Furthermore, feeding them more often doesn’t make them molt faster; instead they will usually spend quite a bit of time fasting as their bodies have told them they’ve had enough. Therefore, feeding your larger specimen more often isn’t likely to lead to a faster growth rate the way it would with slings.

For example, I have a young adult P. cancerides who I fed large dubia roaches to several times a week. After about a month of living the high life, it stopped eating…and didn’t molt for almost five months. Feeding her as much as she would eat definitely didn’t speed up her growth.

There’s a lot of anecdotal evidence from experienced keepers that seems to indicate that “power feeding” really doesn’t apply to these animals. If that’s the case, then, folks who are choosing to feed their spiders multiple times a week aren’t doing their animals any harm.

Why might a keeper decide to feed her spiders more often?

A new keeper may be thinking, why might someone feed their spiders more often when they can get away with once week? There are a few solid reasons a keeper might partake in this practice.

The keeper is trying to grow a female to maturity faster for breeding purposes. If you’re a breeder with a young female you are hoping to mate, you may not want to wait the several years it could take for her to mature on a normal once a week feeding schedule. Breeders will often jack up the temps and feed females as much as they’ll eat in an attempt to get a breedable specimen faster. This is especially true for folks who pay huge amounts of money to import new species with the hopes of producing some of the first captive bred slings. In this case, the goal is to get a viable sack (and big money for the sought-after spiderlings) as quickly as possible.

The keeper is trying to mature a male faster for breeding purposes. So, you have your female ready, and you’re having a difficult time locating a mature male. Just like in the instance above, the keeper may try to mature a sling or juvenile male more quickly through power feeding to get a mature male faster.

The keeper is trying to grow his/her spiders out of the delicate sling stage faster. Personally, this is something I do. Tarantulas are at their most vulnerable during the sling stage, where they are much more sensitive to environmental conditions and husbandry mistakes. Personally, I want my tiniest guys out of this stage as quickly as possible, so I usually give them as much as they will eat until they reach about 1.25-1.5″ in DLS. At this point, I switch them back to a more normal schedule of about twice a week.

The keeper wants his/her tarantula to grow to adulthood faster for aesthetic reasons. The fact is, when you tell people that you have tarantulas, they are expecting to see giant hairy spiders. Unfortunately, even the largest of these awesome beasts start off as tiny, fairly unimpressive slings. Some hobbyists opt to power feed in order to get a large display spider faster.

But does feeding your tarantula often shorten its life?

It should be noted that nothing has been done in terms of scientific research as to how power feeding might negatively impact a spider. Most of what we think we know is postulation and guesswork. Until someone does some controlled experiments comparing sac mates that are power fed to those who aren’t, we’ll have to continue with our own observations and anecdotal evidence.

That said, there are keepers that have been in the hobby for decades who seem to find that the idea of overfeeding a tarantula is simply foolish. Their years of collective experience in keeping and breeding has taught them that these animals do not experience the same health issues snakes or mammals would when fed regularly.

So, now that we’ve heard the benefits of feeding spiders whenever they’ll eat, what are some of the perceived issues surrounding this practice. Below is a list of the supposed cons according to folks who are against it.

- Shortens the lifespan of the tarantula

- Can cause molting issues

- Stretched abdominal skin can rupture more easily

- Some believe it can cause fertility issues in males and females (although this one had been disproved repeatedly)

Now, it must be mentioned that many of these side-effects, like molting and fertility issues, have all been disproved. There are plenty of breeders out there who have fed their Ts often to get them to breeding age, and none have reported issues. As for molting issues, some have argued that in species like Theraphosa stirmi, it can cause bad molts. However, many keepers feed this species as much as it will eat and have no issues whatsoever. Again, this appears to be a myth.

Now, it IS absolutely true that fat spiders are more prone to abdominal ruptures, so this is a very real concern.That said, a properly set up enclosure with the correct amount of substrate and ceiling height would seriously limit the chance of this happening.

But doesn’t “power feeding” reduce lifespans?

The answer is: if it does, it’s usually not enough to worry about. For most species, the only time feeding them more will make a difference on growth rate is when they are slings. As established, they are designed to eat as much as they can during this period, and well fed slings will grow faster than slings fed less often. That said, their growth rates will usually slow down a bit once they put on some size, so the amount of time supposedly sheered off their lifespans would be very short indeed.

Take a look at the charts below. For the first one, I used a hypothetical female tarantula with an average lifespan of 15 years. Due to the longevity of this species, “power feeding” has a very nominal effect on the overall lifespan (the gray area designated by a “?”) In this instance, the amount of time potentially taken off of its life is a matter of months, not years. This is a very small amount of time in the grand scheme of things.

Now, this would be a female with a medium lifespan. Imagine if we were to use a Brachypelma, Aphonopelma, or Grammostola species female. Because they can live 25 years or more, the time power feeding one would take off of its lifespan would be negligible at best.

Personally, I think this is a worthwhile trade-off to ensure my spider better chances earlier in life.

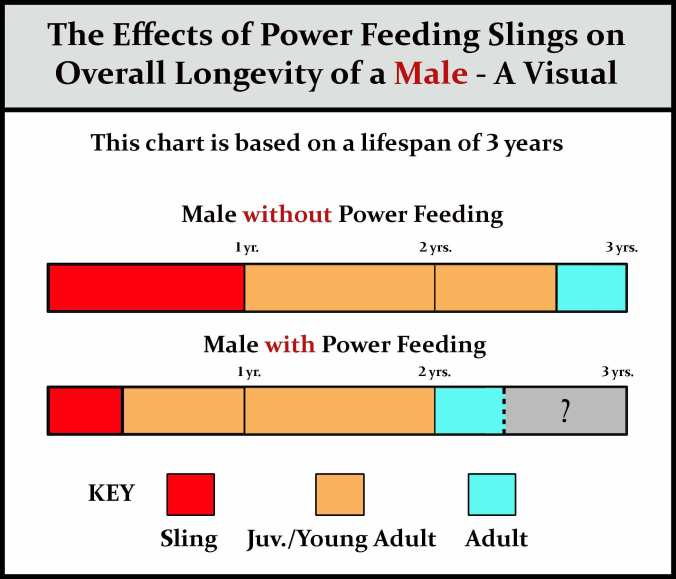

For males, it can be a little bit different. Obviously, males have shorter lifespans as it is, and most will outgrow their female counterparts in the same time span. Therefore, the accelerated growth earlier in the male’s life-cycle may have a more profound effect on its overall lifespan.

In the chart below, we look at a male tarantula with a lifespan of three years. Here, the sped up growth cycle eats away a higher percent of its life. That being said, if you find out that the sling you raised is a male, you don’t have to starve your animal, but a lighter feeding schedule would prolong its life and make up for some of the time lost to power feeding.

(Note: The charts above are meant only as approximations, and many factors, including temperature, diet, and the genes of individual species could impact these estimates.)

Either way, these charts illustrate the fact that the sling stage is actually a very small part of a spider’s life cycle, and power feeding a sling at this point in its life really doesn’t impact the tarantula’s lifespan that much at all.

Also, lets not forget that we are still not sure how long some of these spiders can live. So, if the T above were to die in the span of that gray area at the end, we would have no way of knowing if its lifespan had been shortened by early power feeding, or if there were other factors involved.

Just something to think about.

The Verdict

Honestly, I don’t really believe that “power feeding” applies to Tarantulas, and that there is nothing wrong with feeding your pets as much as they will eat. Worst case scenario, you’ll get a fat T that will fast for a bit.

Could it shorten a T’s life? I suppose, but in most cases, if it did shorten the spiders’ lives, it would be by a nominal amount. Personally, I’d rather risk rushing my tarantula through the fragile sling stage than possibly “prolong” its life by withholding food. As long as proper husbandry is followed, and the animals are kept correctly, there really isn’t any harm to the T and its comfort level.

After all, in the wild they exist to eat, mature, and breed.

And, if a keeper wants to savor every minute with their beloved animal as it grows over the years, who’s to judge if she decides not to cut back on the feeding her. These animals are, for many of us, pets, and it would make sense that we would want them with us as long as possible. If this keeper has no interest in breeding, then it would behoove her to not rush its growth.

To each his or her own.

Reblogged this on Casey's Overnight Cafe and commented:

An excellent treatise on the pros and cons as well as the “whys” and “why-nots” of power feeding captive tarantulas.

LikeLike

Think you might need to change your units of measurement in part 1 of the “How-to”. 🙂 That said… I think I might have been doing this accidently to one of my P. Cambridgei slings. It was already a little bit bigger than it’s siblings at the store and has grown FAR faster than the other P. Cambridgei sling in my care. After reading this I realized that not only is it the closest T to my space heater but I DO feed it at least one medium cricket every two days. It’s my only sling that consistently out-eats both my GBB AND my P. Cancerides… I swear it’s ALWAYS hungry, all the time! 😀 It’s molted twice in my care in a little less than two months and had a huge growth spurt each time. May have to try this once my A. Versicolor sling gets here to try and get it through the “fragile zone” >.< As always, thanks for the article! 🙂

LikeLike

Holy cow…great catch! Yes, 80 degrees Celsius would be just a BIT too warm. 😉 Thanks so much…it is now fixed!

Sound like your P. cambridgei could also be male. Generally, males will grow faster than their female sac mates. And it out-eats a GBB and a P. cancerides? WOW. That is truly impressive, as though two spiders are some of the best eaters in my collection!

It’s amazing how much just a few degrees can do for their appetites. I had a similar situation where I moved one of my P. cancerides to another shelf that just so happened to be a bit closer to the heater and, therefore, warmer. That little gal turned into even more of an eating machine, and ended up molting twice in the time her sac mate molted once.

It’s funny, because I power fed MY A. versicolor when it was a sling for that exact reason. How large of a sling are your receiving? The color changes these guys go through as they grow are amazing.

Thanks for reading a for catching that error!

Tom

LikeLike

No problem! 🙂 The versi arrived today, it couldn’t be more than half an inch… just a tiny blue jumping bean! 😀 Had a heck of a time getting it into it’s enclosure, seems to be quite a bit more nervous than my A. Avic sling is. Some part of me is a bit reluctant to attempt powerfeeding though assuming these are as fragile as everyone says… I have been fortunate to not lose a sling yet (not counting DoAs from dealers anyways). I’m sure a bit of careful watching of the humidity and it’ll pull through though… either way I’m happy to have it finally, between a T. Gigas, two A. Avics, two P. Cambridgei, two P. Irminia, two I. Hirsutum and now this A. Versicolor I’m beginning to think NW Arboreals are becoming a bit of a fixation. 😀

LikeLike

Congrats! That was about the size mine was when I got her. Can those little boogers move or what? 🙂

Don’t feel like you HAVE to power feed it. I found that mine was eating like a champ, and I was very worried that I was going to screw up and end up with a dead sling, so I gave her as much as she would eat. I had just heard so many cautionary tales about SADS (especially with versicolors) that I couldn’t help but to worry.

I ended up keeping mine on the dry side after reading accounts by several more experienced keepers who had great success with them (and no SADS). The general consensus now is that it was the overly-moist, stuffy cages that was killing them all. For years, folk would keep these things wet, restricting airflow in order to keep the humidity up. This is when the versi got the reputation for being fragile and difficult to keep alive.

However, once folks supplied more ventilation and put less of an emphasis on keeping them wet, they started thriving. Something to think about.

You’re definitely developing a New World arboreal obsession! Haha. Have you started eyeing some of the Old World arboreals yet? It definitely sounds like you’re building up to them… 😉

LikeLike

Thank you for the advice, that is quite relieving to hear… I knew my A. Avic sling seemed to be fine without a ton of extra humidity but y’never know. 😀 I do actually have one Old World Arboreal sling… an absolutely STUNNING P. Subfusca Highland. Seems like I’m one of those lucky few that ended up with a “calm” pokie… the only thing that seems to bring out her skittish tendencies is a bit too much light. She’s always responded to prodding and cage maintenance calmly and without issue… but WOW she can teleport! O.O As a courtesy to my roommate (who’s been VERY cool about the whole T collecting thing :-D) I agreed to sell my Old Worlds when I moved in… so my H. Vonwirthi and E. Pachypus went to a buddy of mine that owns a reptile store… I know him well enough to know he’ll give them proper care. 🙂 But I just can’t get rid of my pokie! 😀 Any suggestions for more Arboreals to look into would be much appreciated. 🙂

LikeLike

It’s tough, because if you look up care sheets for avics, many of them STILL say to keep them moist. I had to really start talking to some keepers and researching more current info on the boards. When I chose to keep my versi drier, I was REALLY worried for a bit. But even with the humidity in my house dipping to the teens during my first winter with this .5″ sling, it still thrived.

Man, I’m very jealous of your P. subfusca highland! I’ve been eyeing one for a while, and I just haven’t gotten around to getting one. I currently keep eight species of pokies, so I really need to fill that hole in the collection. Lol I don’t blame you one bit for keeping it..they are fast as heck, but oh so gorgeous.

Awww…the poor E. pachypus. Hahaha. I love my little gals, but I’ve honestly only seen them maybe twice, and once is when I had to house them after they arrived. 🙂

I’ll definitely give some thought to some more New World arboreals and let you know. 🙂

Tom

LikeLike

A lifetime of observing arachnids in general as a casual “fan”, I’m going to say that the spider knows when it is full…and will stop hunting and eating when it gets there…IMO. From what I’ve seen in the short time I’ve been “keeping”, I’m not seeing a ton of difference in behavior…especially in the slings. They (the adults) will gorge if they can, because millions of years tells them that there is a time approaching…soon…where a season of “nothing” is coming. Captivity or not, feeding isn’t part of “learned”, it is genetic instinct. In captivity, the instinct is betrayed by the continual rain of ‘awesome’ from the door above, but they will refuse once they are sated. (How much this is? Not the first clue…they have minds of their own about these things.)

Personally, I feed my slings 2-3 times a week until they “shut the door” or refuse to eat. My adults get fed twice if I’m using smaller lateralis, or once if I’m dumping the porterhouse-dubia-steak on em. 😀

Excellent article as usual! 🙂

LikeLike

I agree completely. When you consider what it’s like for these guys in the wild (and some live in some pretty inhospitable locales), it would make sense that they would be able to gorge themselves when food is plentiful. Like you said, this is an instinct, not “Tom is bored so he’s going to go gorge himself on a bag of chips.” Nature has taught them that when there is food, it is time to eat.

And, considering many are from areas where temps will fall seasonally and prey will become scarce, you also start to understand these mysterious “fasts” some will go on (I’m looking at YOU, my little G. rosea sling!).

I get that some folks worry about their long-term health, and I agree that could be a concern. But I also think that this idea comes from people comparing them to other animals, like snakes, and that’s just not a fair comparison.

I feed mine on the same schedule as you. When they are done eating, they either tell me by closing up shop or by slapping the prey away (which causes me to quickly remove it).

Love the porterhouse-dubia-steak. Ha!

Thanks again!

Tom

LikeLiked by 1 person

So I’m not the only one with a lil rosea sling that has quit eating. At first I thought it was molt time (typical signs: shiny big opisthosoma, refusing food, etc.) but now…two weeks and while the little git looks healthy, just sits around most of the time, and the food is flat out ignored. heh. I drop in once a week now, and if it’s still sitting there 24 hours later…pull it out. (She’s tiny, so it’s pre-killed…which she devoured at first, because living cattle sent her to the lid. heh.)

LikeLike

Unfortunately, I think we’re part of a very large club. 😉 Honestly, I should complain because in the 19 years I’ve had my G. porteri, she has NEVER refused a meal. That is almost unheard of. My little rosea sling? Not so much. She fasted from about October of last year until May of this year. The whole time, she looked plump and like she could possibly molt, but her abdomen never got dark. So, in May, I threw a tiny cricket in…and she ate! She ate twice more after that then…back to fasting. Gotta love them roseas!

Yup, I play the once a week game, too. And every once in a while, I don’t see the cricket and think they ate it, only to find it later. Such as let down. Don’t these little guys know how much we worry?

Ha! My G. pulchripes slings (which ARE eating at the moment…yay) used to run from live prey. They have now grown up a bit and are stone-cold killers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

HAH! No sooner than I get this done, and the little bugger did it.

http://cjpeter.com/?attachment_id=2300

LikeLike

LMAO…and sigh. I used this as a reference link in the T.Keepers group (Scott Templemen’s) on FB, referencing some sling feeding questions and one of the admins slapped me for posting “power feeding”. When I disputed that, she said “I read it, and it promotes power feeding.” I almost asked her if we should have a T-weight-watchers group. gah.

“Religious” doesn’t stop at the doors of other groups i guess. -le’sigh

LikeLike

What?! Hahahahaha. That is hilarious!

Seriously, I tried to write that as impartially as possible, but the more research I did, the less I found to support all of the myths that those against “power feeding” offer up as evidence against it. I guess as it took shape, I found myself addressing more the issue of power feeding being vilified by some.

And, as I tried to show in those charts, if you power feed a sling, how much time are you REALLY decreasing its lifespan? If a person doesn’t want to try it, honestly, that’s TOTALLY fine. I completely understand. However, don’t start judging folks who decide to get that spider out of its fragile sling stage a little faster.

And even if it was “pro power feeding”, why try to stifle the other side of the issue? Sigh…

You’re right, bud…”Religious” definitely doesn’t stop there.

Thanks for the heads up!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I private messaged Templeton (I don’t get in public snits), and he actually responded in the thread…

but once I start seeing “ethics” pop up around animals, I start looking for PETA. I might have to be-bop to the handler group…big group, but much less “focused” if you will on how to TREAT the babies. -gads.

His response in the group thread:

Scott Templeman: My point of view when it comes to powerfeeding is one where there are avenues where it is advantageous, required even… For very rare species and breeding purposes. I have even experimented with what most would consider under-feeding, and the results were… Pretty much the same when it came to a fast growing male species… Except he matured smaller stature. Does that make power – feeding a good idea? No, if only for ethical reasons for the most part.. But occasionally it is required in a tiny fraction of examples.

LikeLike

I avoid the public snits as well, so I don’t blame you one bit.

Ethics…the reason is now “ethics”? As in, “it is ethically wrong to feed a spider a lot food?” Sweet Mary…I can’t stop laughing. Not to be a jerk, but with ALL that’s going on in the world, I honestly can’t believe that someone called power feeding ethically wrong. Man, I love animals…always have. However, this is just a bit absurd.

And by his example, it’s apparently okay if you’re power feeding to bring a rare species INTO A HOBBY to inevitably make money on selling high-priced slings, but not okay if you want to possibly usher your pet through a vulnerable period.

Really?

Well, no use even debating this any further. I’m off to church to ask for forgiveness for possibly taking a few months off my spiders’ lives by giving them a safe home and all the crickets they can eat. Pray for me…

🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m agnostic. I’ll think happy thoughts for you. And 1000% agree with your take. That was mine…including the jaw dropping wide as I read it.

The funny thing is, the group is stuffed to the GILLS with tarantulas munching on every conceivable bit of LIVING cattle you can think of. The hypocrisy is almost enough to bounce. But I don’t publicly snit that stuff as it is absolutely just not worth the time or effort. 😀

LikeLike

Crap…as am I. Guess I’d better just live with my unethical behavior.

Seriously, I’m so glad that you shared this with me. I can’t even be upset because the word “ethics” just made the entire thing silly. It just bothers me that folks with a bit of experience can spout off nonsense as if it’s fact, and those new to the hobby could believe it. Ugh.

Ha! And you’re absolutely right…what about the roaches?? The crickets?? I mean, where do you draw the line? 🙂

Now, don’t you DARE feed those Ts of yours for at LEASE another week. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

On it. 😀

LikeLike

Just got booted from the T-keeper group. Sent you mail with the thread. Thought you’d get a kick out of it. Regarding soft fangs and the poor fluffy bunnies that T’s all are. -snicker.

LikeLike

I just responded. I’m floored. I can’t stand when people try to turn approximations into “rules” and speculation into “fact”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I recently got my very first Ts this past December (all slings) and I’ve been feeding them every other day based on what you said in your videos on sling care (which I watched a million times!), and I live in San Diego and somehow my sling shelf often hits 78° even though my space heater is only set to 70 and doesn’t run often, and they’re all growing so much faster than I expected. One person I follow on Instagram has two species about the same size that I have, she’s had them since August and they’ve only molted once whereas all of my slings except one have molted twice since December! I wondered if she was barely feeding hers or something and I recently saw her caution someone else against feeding often, and it all made sense. The other person had a G pulchra that grew quite considerably in about 6 months.

I wish there was more scientific evidence regarding this issue, but it makes sense to me that you can’t compare spiders to snakes and it doesn’t make sense to apply snake power feeding issues to spiders.

LikeLike

I think that is ultimately well said, that it’s down to personal preference and opinion.

For those that are against it on the grounds of it being unethical I would suggest that feeding not so often like once a week, once a month or less could be seen as less ethical than feeding every day as anyone who keeps tarantulas will know that you can’t force them to eat, you can offer them food but they will only eat it if they want to thus ultimately the choice to eat is the tarantulas and feeding less often is taking some of that choice away from the spider.

Also I totall understand keepers powerfeeding during the sling stages to get it to a less vulnerable stage asap, some rare species can cost upwards of £500 for a sling and all slings can be notoriously difficult to raise in the sense that with them being so small, delicate & other vulnerabilities that there’s so many factors that can cause a sling to die and most of these issues can overcome a sling that rapidly that usually the first sign of an issue is finding your sling in death curl and has already passed away.

This can happen to all keepers irrespective of experience. I’ve previously lost slings and I know many other highly experienced keepers to lose slings for no apparent reason when they’ve provided it with care to the letter. It’s nature and the reason why egg sacks can contain hundreds even thousands of offspring because in nature only a small percentage of eggs laid will eventually grow and mature into breeding adults to complete their lifecycles.

LikeLike

Thanks, Matthew! The biggest issue with small slings is they lack the waxy layer that prevents dehydration. That makes them more susceptible to sudden deaths.

LikeLike