Or, how to learn to stop worrying and just feed your tarantula when it’s hungry.

Power feeding: The act of accelerating an animal’s growth by increasing temperatures and the amount and/or frequency it is fed.

If you’ve been in the hobby for any amount of time, you’ve likely been privy to a debate between hobbyists about the virtues or dangers of feeding tarantulas too much. Although a less incendiary topic than handling, this subject of “power feeding” still manages to elicit some strong views as folks are seemingly split over whether this is a harmless practice or a detriment to tarantulas’ health and longevity.

I’ve had many new hobbyists contact me over years needlessly worrying about whether or not they are going to overfeed their tarantulas or concerned with this horrible thing called “power feeding” that they’ve heard about and been told to avoid. When I tell folks to feed their slings as often as they want, I often get a response along the lines of, “But isn’t that power feeding? Won’t that shorten the life of my T?” I’ve even be trashed by a concerned hobbyist that told me that feeding my animals more than once a month constituted animal abuse.

Okay then…

In many ways, the term “power feeding” has become a bit of a dirty phrase to some in the hobby … which is ironic, as many informed and experienced hobbyist would argue that it doesn’t even apply to tarantulas. The term actually originated in the herp hobby, particularly when breeding color morphs of ball pythons. While snake breeders have used power feeding for decades in order to quickly get their specimens to breedable size, the practice has been recognized for having adverse effects on the animals’ health. Therefore, the assumption is that the same practice would also be harmful for arachnids.

Unfortunately, comparing snakes to tarantulas, two very different organisms, doesn’t work in this instance.

The fact is, many expert keepers feel that feeding your tarantulas as much as they will eat has no negative impact on their health and longevity. Although much has been said about the negative impacts it could have on an animal, they point to lack of scientific proof (and point to mounds of keeper anecdotal data that seems to dispel this idea). They argue that the worst that can happen from feeding a spider all it will eat is a fat tarantula that will fast for a while.

Many inexperienced hobbyists will understandably err on the side of caution and avoid this practice for the sake of their animals’ well being. They will unfortunately read about “power feeding” on some website and immediately worry that they might overfeed their pet. Due to this misinformation, they feel strongly that, by allowing their animal to “overindulge”, they are putting its health and lifespan at risk.

However, are they really extending their tarantulas’ lifespans, or is the idea of “power feeding” tarantulas only a myth?

First off, how would one “power feed” tarantulas?

Before we get any further, it’s important to define what supposedly constitutes “power feeding.” Although most folks think power feeding is just increasing the amount of food you give to your tarantula, it’s not quite that simple. To truly power feed, you need to do two things:

- Increase the temperature: To get the quick growth “power feeding” is meant to promote, you also need to stimulate the T’s metabolism. This is done by increasing the temperatures to the low 80s for most species. Basically, the warmer the surroundings, the faster your tarantulas will grow. If the temperature in your home is dipping to 68° F (20° C), then your T will not have the fast metabolism required for quick growth. For true “power feeding”, it’s more about speeding up the metabolism than just pumping your T full of food.

- Feed the tarantula as much as it will eat: With its metabolism sped up, it’s now time to increase the frequency food is offered. This can be every day or every couple days, depending on the size of the meal. If you give your .5″ sling a medium cricket to scavenge feed on, it might only be need to be fed a couple more times before it’s ready to molt. If you are feeding smaller, more manageable-sized prey, then it may eat every day to every other day.

It’s really that simple. Unfortunately, many folks will try to feed their Ts more without providing a warmer environment. Doing so will likely result in a fat T who takes its time molting (trust me … I’ve done it). It’s important to remember that higher temperatures have more to do with growth rate than how often you feed.

Now, some folks seem to consider it “power feeding” when you feed a slings multiple times a week. Personally, I think that’s a bit ridiculous. Many tarantulas are at their most voracious when they are slings, and this is a great time to make sure they get as much food as they can take. If the temperatures are high enough, and they are well-fed, this will lead to faster growth (and get your animal out of the delicate sling stage earlier).

Many hobbyists reason that tarantulas know what they are doing; if they want to eat, they’ll eat. If they’re not hungry, they won’t. In the wild, it behooves a sling to grow as fast as possible to outgrow this vulnerable stage. As slings, these animals are at particular risk from predators and the elements. During times when prey is plentiful, they would likely eat as much and as often as possible in order to foster faster growth.

So, why wouldn’t this hold true in captivity?

Even in captivity, tarantulas are most vulnerable during their sling stage. At this time, they are prone to dehydration and extra susceptible to environmental factors like humidity and temperature. Many, if not most, of the sudden deaths reported by keepers are spiderlings. Therefore, many keepers will feed their sling much more often

Personally, I tend to feed my slings as much as they’ll eat in the summer when the temps are around 80 or so for just this reason. Once the sling hits about 1.25-1.5″, I slow the feeding down to one or twice a week (depending on the size of the prey). This has worked very well for me.

Is feeding slings as much as they will eat really “power feeding”? Most experienced keepers would argue NO. Eating while food is available is a natural adaptation that allows for them to quickly grow in the wild.

But what about the adults? Again, many would argue that the “power feeding” really doesn’t apply, at least not in the way it does with snakes. Keepers have discovered that tarantulas will only eat until a certain point, then they stop and prepare to molt. Furthermore, feeding them more often doesn’t make them molt faster; instead they will usually spend quite a bit of time fasting as their bodies have told them they’ve had enough. Therefore, feeding your larger specimen more often isn’t likely to lead to a faster growth rate the way it would with slings.

For example, I have a young adult P. cancerides who I fed large dubia roaches to several times a week. After about a month of living the high life, it stopped eating…and didn’t molt for almost five months. Feeding her as much as she would eat definitely didn’t speed up her growth.

There’s a lot of anecdotal evidence from experienced keepers that seems to indicate that “power feeding” really doesn’t apply to these animals. If that’s the case, then, folks who are choosing to feed their spiders multiple times a week aren’t doing their animals any harm.

Why might a keeper decide to feed her spiders more often?

A new keeper may be thinking, why might someone feed their spiders more often when they can get away with once week? There are a few solid reasons a keeper might partake in this practice.

The keeper is trying to grow a female to maturity faster for breeding purposes. If you’re a breeder with a young female you are hoping to mate, you may not want to wait the several years it could take for her to mature on a normal once a week feeding schedule. Breeders will often jack up the temps and feed females as much as they’ll eat in an attempt to get a breedable specimen faster. This is especially true for folks who pay huge amounts of money to import new species with the hopes of producing some of the first captive bred slings. In this case, the goal is to get a viable sack (and big money for the sought-after spiderlings) as quickly as possible.

The keeper is trying to mature a male faster for breeding purposes. So, you have your female ready, and you’re having a difficult time locating a mature male. Just like in the instance above, the keeper may try to mature a sling or juvenile male more quickly through power feeding to get a mature male faster.

The keeper is trying to grow his/her spiders out of the delicate sling stage faster. Personally, this is something I do. Tarantulas are at their most vulnerable during the sling stage, where they are much more sensitive to environmental conditions and husbandry mistakes. Personally, I want my tiniest guys out of this stage as quickly as possible, so I usually give them as much as they will eat until they reach about 1.25-1.5″ in DLS. At this point, I switch them back to a more normal schedule of about twice a week.

The keeper wants his/her tarantula to grow to adulthood faster for aesthetic reasons. The fact is, when you tell people that you have tarantulas, they are expecting to see giant hairy spiders. Unfortunately, even the largest of these awesome beasts start off as tiny, fairly unimpressive slings. Some hobbyists opt to power feed in order to get a large display spider faster.

But does feeding your tarantula often shorten its life?

It should be noted that nothing has been done in terms of scientific research as to how power feeding might negatively impact a spider. Most of what we think we know is postulation and guesswork. Until someone does some controlled experiments comparing sac mates that are power fed to those who aren’t, we’ll have to continue with our own observations and anecdotal evidence.

That said, there are keepers that have been in the hobby for decades who seem to find that the idea of overfeeding a tarantula is simply foolish. Their years of collective experience in keeping and breeding has taught them that these animals do not experience the same health issues snakes or mammals would when fed regularly.

So, now that we’ve heard the benefits of feeding spiders whenever they’ll eat, what are some of the perceived issues surrounding this practice. Below is a list of the supposed cons according to folks who are against it.

- Shortens the lifespan of the tarantula

- Can cause molting issues

- Stretched abdominal skin can rupture more easily

- Some believe it can cause fertility issues in males and females (although this one had been disproved repeatedly)

Now, it must be mentioned that many of these side-effects, like molting and fertility issues, have all been disproved. There are plenty of breeders out there who have fed their Ts often to get them to breeding age, and none have reported issues. As for molting issues, some have argued that in species like Theraphosa stirmi, it can cause bad molts. However, many keepers feed this species as much as it will eat and have no issues whatsoever. Again, this appears to be a myth.

Now, it IS absolutely true that fat spiders are more prone to abdominal ruptures, so this is a very real concern.That said, a properly set up enclosure with the correct amount of substrate and ceiling height would seriously limit the chance of this happening.

But doesn’t “power feeding” reduce lifespans?

The answer is: if it does, it’s usually not enough to worry about. For most species, the only time feeding them more will make a difference on growth rate is when they are slings. As established, they are designed to eat as much as they can during this period, and well fed slings will grow faster than slings fed less often. That said, their growth rates will usually slow down a bit once they put on some size, so the amount of time supposedly sheered off their lifespans would be very short indeed.

Take a look at the charts below. For the first one, I used a hypothetical female tarantula with an average lifespan of 15 years. Due to the longevity of this species, “power feeding” has a very nominal effect on the overall lifespan (the gray area designated by a “?”) In this instance, the amount of time potentially taken off of its life is a matter of months, not years. This is a very small amount of time in the grand scheme of things.

Now, this would be a female with a medium lifespan. Imagine if we were to use a Brachypelma, Aphonopelma, or Grammostola species female. Because they can live 25 years or more, the time power feeding one would take off of its lifespan would be negligible at best.

Personally, I think this is a worthwhile trade-off to ensure my spider better chances earlier in life.

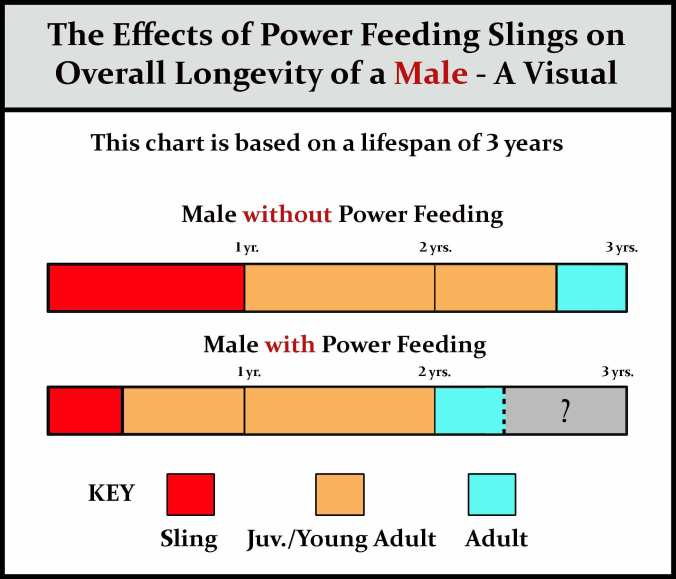

For males, it can be a little bit different. Obviously, males have shorter lifespans as it is, and most will outgrow their female counterparts in the same time span. Therefore, the accelerated growth earlier in the male’s life-cycle may have a more profound effect on its overall lifespan.

In the chart below, we look at a male tarantula with a lifespan of three years. Here, the sped up growth cycle eats away a higher percent of its life. That being said, if you find out that the sling you raised is a male, you don’t have to starve your animal, but a lighter feeding schedule would prolong its life and make up for some of the time lost to power feeding.

(Note: The charts above are meant only as approximations, and many factors, including temperature, diet, and the genes of individual species could impact these estimates.)

Either way, these charts illustrate the fact that the sling stage is actually a very small part of a spider’s life cycle, and power feeding a sling at this point in its life really doesn’t impact the tarantula’s lifespan that much at all.

Also, lets not forget that we are still not sure how long some of these spiders can live. So, if the T above were to die in the span of that gray area at the end, we would have no way of knowing if its lifespan had been shortened by early power feeding, or if there were other factors involved.

Just something to think about.

The Verdict

Honestly, I don’t really believe that “power feeding” applies to Tarantulas, and that there is nothing wrong with feeding your pets as much as they will eat. Worst case scenario, you’ll get a fat T that will fast for a bit.

Could it shorten a T’s life? I suppose, but in most cases, if it did shorten the spiders’ lives, it would be by a nominal amount. Personally, I’d rather risk rushing my tarantula through the fragile sling stage than possibly “prolong” its life by withholding food. As long as proper husbandry is followed, and the animals are kept correctly, there really isn’t any harm to the T and its comfort level.

After all, in the wild they exist to eat, mature, and breed.

And, if a keeper wants to savor every minute with their beloved animal as it grows over the years, who’s to judge if she decides not to cut back on the feeding her. These animals are, for many of us, pets, and it would make sense that we would want them with us as long as possible. If this keeper has no interest in breeding, then it would behoove her to not rush its growth.

To each his or her own.