Or, the very basic information every new tarantula keeper needs to know.

Anyone who has followed my blog or YouTube page has likely heard me talk about the first tarantula I ever acquired. About 20 years ago, after being an arachnophobe for my entire life, I decided that I would get a tarantula to help me get over my irrational fear. This was an animal that fascinated me as much as it terrified me, and I was hoping that handling a big, hairy spider would be an eventual cure. Finding one for sale in the Bargain News, I drove to a fellow exotic pet keeper’s home to procure my new pet. $20 later, I was the proud owner of Grammostola porteri (which I knew only as a “Rose Hair” tarantula). Although I had several dozen snakes at the time, this fluffy little spider was the biggest “oddity” in my collection, and folks often asked to see her when they visited

The fact that this tarantula survived all of my husbandry missteps and general arachno-ignorance those first few years (there wasn’t a lot of great information back in the mid-’90s!) is a testament to just how hardy this species is. Every mistake that could be made, I likely made it, and I truly feel terrible for my poor girl … hence why she has a fancy cage kept right in the center of my vast collection now!

I spend a lot of time talking to new keepers, and when I get asked questions that they think might be foolish or obvious, I try to point out that it really doesn’t feel like that long ago that I had the very same questions. We all start somewhere and, for some of us, many mistakes were made along the way. After doing some reminiscing about my beginnings in the hobby, I thought it might be fun to put together a list of some of the information I wish I knew back then along with some anecdotes about by own missteps and misinformation. With any luck, this will be a fun and informative way for those new to the hobby to learn some basic information about these fascinating creatures while I share some personal (and sometimes embarrassing) anecdotes. For those who are more established, perhaps you will have some stories of your own to add…

And now, things I wish I knew when I first started keeping Ts!

A tarantula on its back is not dead; it’s simply molting. I worry that this misconception has lead to much misery and more than a few dead spiders. During my first year keeping my G. porteri, I discovered her on her back one morning. I called my wife over, and we were both very upset that I had apparently lost my spider. As luck would have it, I had to go to work, so I left her in her enclosure with the full intent of burying her later. When I returned home that night, I opened her cage and stared in total confusion. Not only was my girl still alive, there were now TWO tarantulas in the enclosure!

My L. itabunae just moments after fully casting off its old exoskeleton.

It took me a few minutes to realize that my T hadn’t miraculously spawned a duplicate a-la Gremlins; she had molted her exoskeleton. I had come dangerously close to burying my new pet alive. Sadly, I’m not the first keeper to experience this, and I’ve heard many horror stories about owners who mistakenly tossed their pets thinking them dead. When tarantulas molt, they turn onto their backs for the process. If you see your tarantula on its back, there is no need to panic. Sit back, relax, and enjoy one of nature’s most fascinating events.

Mature males live far shorter lives than females. The second tarantula I ever bought was an adult Aphonopelma seemanni that I acquired at a reptile convention. I took my new pet home, built him what I thought was an awesome enclosure with deep substrate, a pre-made burrow in florist’s foam, and a water dish. I put it in its new home and waited for it to acclimate and eat.

Well, it never did. Instead, it spent all of it’s time climbing the enclosure walls in a seemingly endless effort to escape. I couldn’t figure out what I had done wrong, and I worried that my husbandry was leading to his restlessness. My fears were seemingly realized when, several months later, my new pet curled up and died.

It was years before I stumbled onto an article about spiders that helped me to understand what really happened. My A. seemanni had been a mature male at the end of its life cycle. Many mature male spiders don’t eat ever again and spend all of their time wandering and looking for a female. At this point, they are on borrowed time; they will either be devoured by the female during copulation, or die of old age. A dealer had likely unloaded this specimen on me as it had either already bred or he didn’t have use for it.

Over the past several years, I’ve talked to many folks who were either sold a mature male, or had a sling mature into one and had no idea why it was restless and wouldn’t eat. This can be very upsetting to folks who blame their husbandry for nature taking its course.

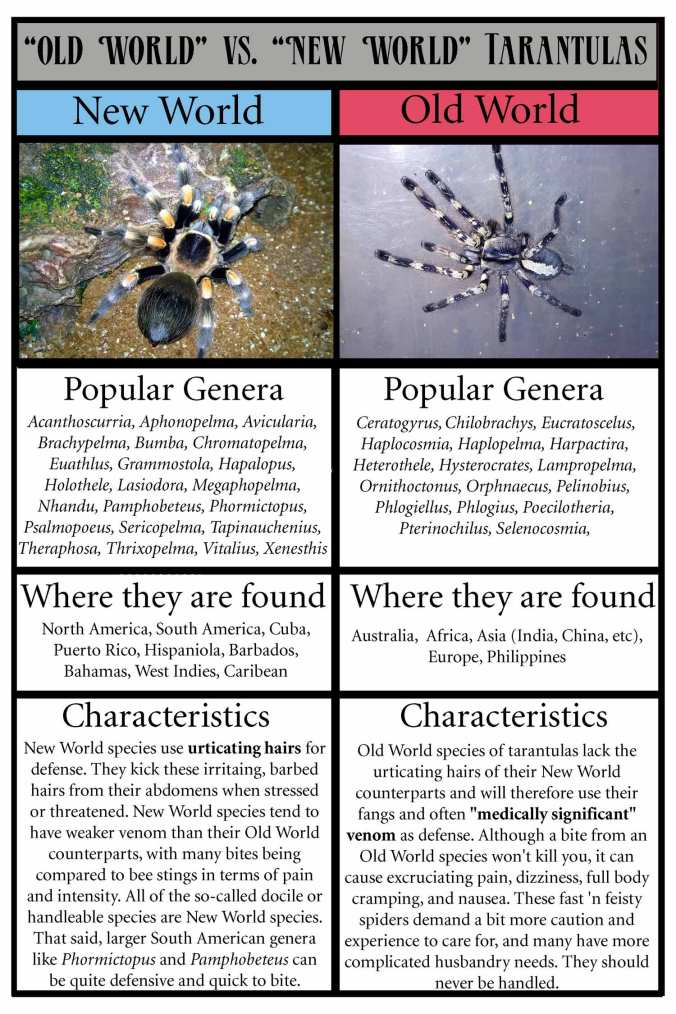

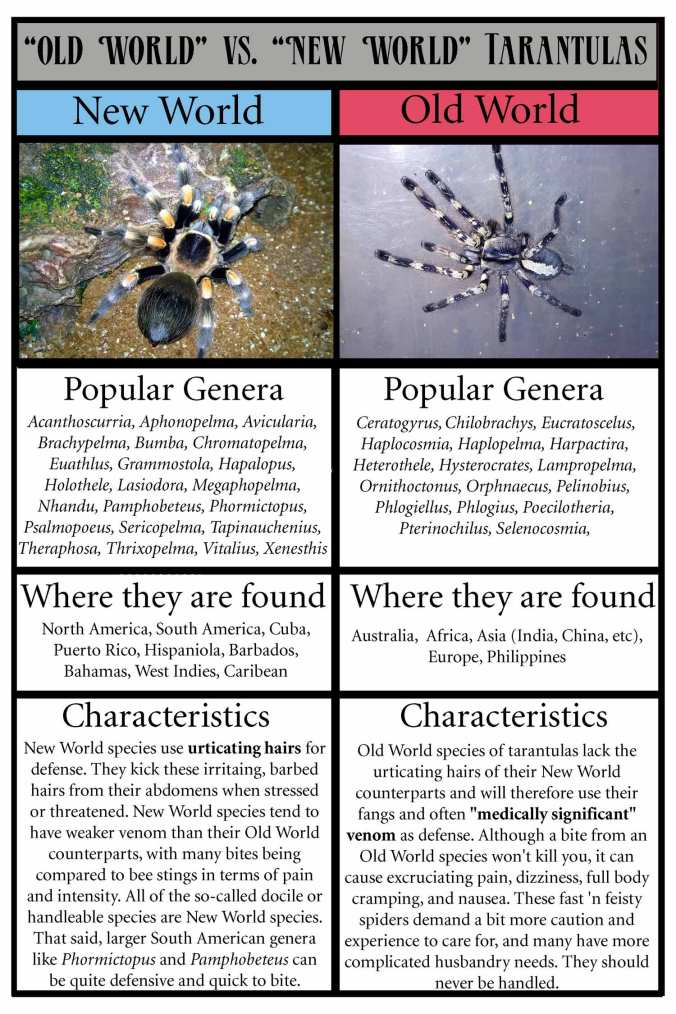

There are major differences between Old World and New World tarantulas. For years, I thought that a tarantula bite was like a bee sting. Luckily, this wive’s tale didn’t end up biting me (no pun intended) in the can. At the same show I bought my A. seemanni at, a dealer was selling a magnificent and terrifying spider labeled “Thailand Black Tarantula.” This large ebony beauty was in a five gallon tank, and it was baring its fangs and spastically slapping at anything that moved (which, in this crowded show, was a lot). I was totally enamored with this animal, and came very close to buying it. Although my wife worried about it’s temperament, I assured her that if it did bite me, it would only be about as bad as a bee sting.

WRONG!

The fact is, HAD I bought that T, and HAD it bitten me, I would have been in for a very nasty surprise. As an Old World species, this tarantula’s bite was medically significant. Although the bite wouldn’t have killed me, I would have been in excruciating pain and suffered other complications like cramping, nausea, and vomiting.

New World species, or tarantulas from North America, South America, and the Caribbean islands, kick urticating hairs from their abdomens as a means of defense. These barbed, irritating hairs get caught in skin, eyes, and nasal passages causing extreme discomfort. New World species have weaker venom, and in many instances, their bites are about the same as a bad bee sting. However, the hairs can be just as nasty and effective.

Old World species of tarantulas (Ts from Asia, Africa, Australia, etc) on the other hand, lack the urticating hairs of their New World counterparts and will therefore use their fangs and more potent venom for defense. Although a bite from an Old World species won’t kill you, it can cause excruciating pain, dizziness, full body cramping, and nausea. Simply put, the can put a real hurtin’ on you. These fast ‘n feisty spiders demand a bit more caution and experience to care for.

I still talk to many folks who are new to the hobby that don’t realize that the “bee sting” comparison is a myth and don’t know the difference between New and Old World tarantulas. Even more disconcerting, I have many try to tell me that they’re not worried about being bitten by a T because it can’t kill them. Yikes. For those interested in learning more about tarantula bites, you can check out the article “A Word About Tarantula Bites”.

You don’t have to handle your tarantulas to be a “real” keeper. When folks find out that I have tarantulas, one of first questions they usually ask is, “do you hold them?” Back when I first got my G. porteri, my friends and family were constantly asking when I would handle her, and I’ll admit to feeling like a bit of a chicken for having never attempted it. After all, that was the point I got her, right?

Finally, the day came. Mustering up all of my courage, I sat her enclosure on my floor, opened it up, and set my hand inside. Using my other hand and a paintbrush, I carefully poked her back legs. With a speed I had never seen from her before, she wheeled around and latched onto the brush with her legs and fangs.

And this sudden violence, a feeding response most likely, shocked me so badly, that I actually passed out. Yup, like out cold.

I woke up a bit later, confused,light-headed, and slumped against the wall, to find my girl perched right at the lip of her enclosure almost as if she was laughing at me. I regained my composure, shooed her back into her cage, and decided that was the last time I would ever attempt to hold a tarantula.

Since that embarrassing experience, I’ve completely overcome my fear of spiders, and I’ve actually held a few of them without incident. However, I choose not to handle them anymore as they get nothing out of it and I know that if I get bit, I’m likely to toss the T, hurting or killing it.

Euathlus sp. red after she crawled out of her enclosure and into my hand. Note: I normally do not handle my Ts

Now, can you hold your pet? If you’ve done the research and have a tractable specimen, of course. However, handling is certainly not mandatory, and many serious keepers have a hands-off policy with their arachnids. I’ve spoken to many new keepers who seem to think that all “expert” tarantula keepers hold their animals, which is definitely not the case. It’s personal decision best left up to the responsible keeper to decide.

Care sheets and their “ideal” temperatures are total nonsense. When I first acquired my G. porteri, I got a tri-folded care sheet from a convention that supposedly detailed the correct husbandry for this species. This document mentioned “ideal” temperatures in the 8os and (wait for it) humidity levels around 80%. Even worse, it suggested using heat lamps or heat rocks for added warmth and recommended spraying the T and its enclosure once a week.

Of course, this is a species that does well in temps in the mid 60s, so this ideal of 80 is nonsense. At the time, I didn’t realize that, so I used to keep the enclosure dangerously close to one of my snake’s heat lamps to keep it nice and warm. It was a minor miracle that I didn’t fry my poor spider doing this, as the heat could have very well have dehydrated my G. porteri.

Even worse, this guide made me think that I had to keep my spider moist, when in fact, this species abhors moisture. For a while, I kept half of the substrate in the enclosure moist, as I thought that this species needed high humidity. It was only after I noticed that she seemed to avoid the wet areas like the plague that I stopped the needless spraying and just started using a water dish.

As it stands, this bogus care sheet led to me accidentally torturing my poor spider with inhospitable conditions (although it could have been much worse). The fact is, generic care sheets usually do more harm than good, and anything mentioning “ideal” temperatures or humidity requirements should immediately tossed in the garbage. I would be willing to bet that many tarantulas are lost due to folks obsessing over false temperature and humidity requirements. Pet stores will often try to sell folks supplementary heat items, like lamps, heat rocks, and mats, and the fact is, these can prove deadly to tarantulas. In most cases, no supplementary heat is needed; they do fine at room temperature.

For more on temperature and humidity, check out “Humidity, Temperature, and Tarantulas“. Or discover more about why care sheets are to be avoided in “Tarantula Care Sheets – an Unnecessary Evil”.

When a tarantula buries itself, there’s no need for panic. Although I never had a problem with my G. porteri burrowing, this became a issue for me when I got my first slings. After about a month of watching my Lasiodora parahybana sling take down every prey item I dropped into its enclosure, I awoke one morning to discover that it had completely closed off the entrance to its den.

Was this purposeful? Had the den caved in? Was it dead? How would it eat?

As the days passed with no sign of my LP, my anxiety grew. I was convinced that the little guy was dead, and I even made the terrible mistake of trying to push a roach into the area I thought to be its webbed up its den entrance (something one should never do). I continued to keep a corner of the substrate moist, and just assumed that I had lost my first sling. Luckily, after a bit of research, I learned that this was normal behavior, and I decided to leave the poor thing along. Sure enough, about a month later, it reopened the mouth of its burrow and sat at the top, hungry and a bit larger.

The fact is, when a tarantula buries itself, it’s the T’s way of putting up the “Do Not Disturb” sign. This is a very natural occurrence, and the keeper just has to trust that their spider knows what it’s doing. It’s not buried alive, it’s not starving, it’s not dead … it just wants to be left alone for a bit. Still don’t believe me? Check out “Help…My Tarantula Buried Itself!”.

Tarantulas can be terrestrial, arboreal, or fossorial. Back when I first got into the hobby, I was heavily into snakes and attended many reptile conventions. At these events, there were always a few dealers who were peddling tarantulas with most displaying them in large terrariums to garner a bit of extra attention. I keenly remember that a few of the species seemed particular ornery as they sat in the center of barren enclosures on a couple inches of vermiculite, angrily slapping at everything.

I now realize that part of the problem was that many of these species were being kept incorrectly, either due to display purposes or just bad husbandry. Back then, I could remember dealers telling folks that all species do well in a 10 gallon aquarium with a couple inches of substrate. This one size fits all approach to tarantulas was of course quite wrong.

I now know that there are three basic types of tarantulas.

Terrestrial tarantulas live on the ground and do well with a few inches of substrate and a hide (often a piece of cork bark). It should be noted that many terrestrial species will burrow as slings, but will outgrow this behavior and stay out in the open as they mature.

Fossorial tarantulas live in burrows under ground. These species need deep substrate to construct their homes, and do not need to be offered hides as they will dig their own. Many fossorial species will spend the majority of their time underground, proffering their keepers only glimpses of their front legs as they wait for prey.

Arboreal tarantulas live off the ground in trees in their natural habitat. These species need more height for their enclosures and branches or cork bark to climb on. For most, substrate depth isn’t important as they will spend the majority of their time on the decorations or walls.

In the same vein, there are also arid species that require dry substrate and moisture-dependent species that need moist substrate to thrive. A keeper who does his or her research will be careful to consider all of these factors when setting up a proper home for a new spider.

Tarantulas are amazing escape artists. This one almost bit me in the butt with my A. seemanni. The first tank I put her in was meant for fish, so the acrylic top had a smallish hole in it for a filter. Considering that this tarantula was about 5″ long, I figured there was no way he could fit through the hole.

Boy was I wrong.

While at work, I got a frantic call from my mother who was babysitting my son at my apartment. Mom was terribly arachnophobic, and it took a lot of convincing to get her to come to my home because of the spiders. Well, while she was there, my A. seemanni squeezed out of the hold and was sitting right on top of the enclosure when she entered the room. She grabbed her keys and my son and refused to come back.

Although the story is quite funny now, this oversight on my part could have led to the death of my spider. The fact is, these animals can squeeze through any gap that will allow their carapaces to fit through. They are also quite strong and able to lift up the corners of unsecured tank tops. Do you have a fancy enclosure with wire mesh vents? Well, you might want to replace them as tarantulas can chew right through them with little effort.

When choosing a home for your new acquisition, it’s always important to make sure that it is secure enough to adequately contain your new ward.

A wire mesh vent that my L. itabunae nearly chewed completely through.

Tarantula common names, although sometimes cool, are often quite useless. For years, I referred to my G. porteri as my “Rose Hair” or simply my “rosie”. I was used to referring to my pets by breed names, like labrador retrievers, pit bulls, etc for my dogs, or common names for snakes, like boa, corn, or king. It never occurred to me that I should ever have to learn the scientific name of anything.

Unfortunately, the hobby is rife with overlapping, inaccurate, or just plane bogus common names for the various species of tarantulas available. There are so many “bird eaters” and “striped legged” spiders currently available that it’s enough to make a person’s head spin. In some instances, species don’t have common names at all. The fact is, those truly into the hobby only use the scientific names when describing their animals. Most tarantulas dealers also list their stock alphabetically by scientific name, with many not including the common name at all.

Now, that’s not to say that there is anything wrong with using common names. It’s just with the amount of overlap and the fact that some are literally made up by dealers, the best way to accurately identify a tarantula (or theraphosidae) is by their scientific names. Those interested in learning a bit more about scientific names can check out “Tarantulas – The Importance of Learning (and Using!) Scientific Names”.

Tarantula can drink just fine out of water dishes. For the first several months I kept my G. porteri, I had a chunk of natural sponge in its water dish. After all, I was told that tarantulas couldn’t drink from just a normal dish, and that they needed a sponge to “suck the water out with their fangs.”

I can’t even begin to explain how embarrassingly wrong this is.

First off, tarantulas have mouths to drink and eat. Their fangs are meant to inject venom, not to suck up water like two pointy straws. Trust me, I’ve seen mine drink directly from their water dishes many times. Secondly, sponges are incredibly unsanitary and will soon turn a water bowl into a veritable petri dish of bacteria. They serve no purpose in a tarantula’s home.

This hobby is ridiculously addictive. If you’ve been keeping tarantulas for a while, this needs no further explanation. If you’re brand new to this amazing hobby, consider yourself warned…

Did I miss anything? What do you wish you knew before getting into the hobby? Please, chime in using the comments section!